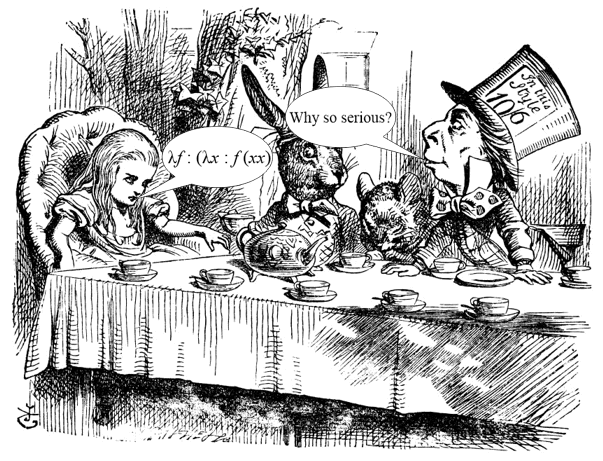

Functional programming has a reputation for being notoriously hard to understand. In this post, we examine its basic principles, abstractions, and building blocks. Hopefully, after reading this, you will be able to decide for yourself whether you really want to embark on a trip into this wonderland.

Down the Rabbit Hole: The Foundational Principles

The principles discussed below have a profound impact on how the functional programs are designed. Traditional object-oriented design is focused on entities, their behaviors, and the relations between them. On the other hand, the functional world data is completely separated from behavior. Programs written with the functional approach are designed as workflow pipelines of data transformations. The functional composition is probably the central principle here, on which most of functional abstractions are based.

Immutability and Referential Transparency

Despite a widespread belief, it is not the presence of lambdas, and even lambda calculus, that makes programming functional. The truth is embarrassingly simple. In a purely functional program, all data structures should be immutable, and functions must be referentially transparent (free of side effects). A referentially transparent expression could always be replaced with its value without changing the result of the program. This means that, like mathematical functions, such functions should always return the same value when called with the same set of arguments. But there is a little quirk. To be able to participate in functional composition, all functions should have only one argument. We will see how to deal with this below using currying.

First-class functions

Having first-class functions means that functions could be returned as a value or passed as arguments. In this case, lambdas or anonymous functions make sense. The existence of lambda-functions that could be defined elsewhere implies the existence of lexical closures. In the functional languages with side effects, lexical closures may become a basis of poor man’s encapsulation. But more often, first-class functions are employed as the mechanism for another type of abstraction: higher-order functions.

Recursion and Corecursion

Recursion is a way of solving problems by representing it as a combination of some base case and a smaller version of the same problem. Usually, recursion is implemented through self-referencing function calls or through mutual recursion. While recursion starts with the last step and continues until the base case is achieved, corecursion starts with the base case and continues until the first step. Depth-first and breadth-first tree traversal algorithms are examples of recursion and corecursion respectively.

Higher-order functions

Higher-order functions are functions that accept other functions to use them as a part of the algorithm. They may be considered as an abstraction device similar to the template method in OOP. The map is a usual example.

In the context of functional programming, combinators are the higher-order functions that do not have dependencies on the outer context (do not have free variables) and use only function applications to produce results. Y is a curious combinator which allows achieving self-recursion in languages that do not support referring to a function by its name from its own code. In general, combinators are used to hierarchically organize abstractions, reducing code complexity.

Folding

In purely functional languages, the mutation is prohibited, and we can not

create a loop that modifies a variable through its iterations. To iterate, we

can only rely on recursion. A higher-order function called

fold (also known

as reduce) serves as the generalization of this recursive approach to iteration. It

takes a recursive data structure, such as a list, along with a combining

function, and returns a value that combines all the elements of the given data

structure. Recursion may be implemented in two different ways, by

combining the first or the last element of the data structure with the

result of the combination of the rest. There are two corresponding kinds of the

fold: the right (foldr, for example 1 + [2 + [3 + [4 + 5]]]) and the left

(foldl, for example [[[1 + 2] + 3] + 4] + 5). The direction of folding may be

important if the supplied combining function is not commutative. Tail-call

optimization is required to circumvent

the issue of stack overflow on large inputs.

Functional composition

Because functions should not produce side effects, there is little sense in

sequential function evaluation. And indeed, functional languages generally

allow only one statement per function. Although, if pattern matching is

involved, this statement may contain more than one path of execution. One of the

ways to achieve sequential evaluation in a single statement is to compose

functions. For instance, while imperative programmers write f1(); f2();,

functional programmers write f2(f1());. Thus, the function

composition

becomes the crucial primitive used to make abstractions in the functional world.

Functional programmers invented many ways to compose various

things with each other. For example, Haskell has

the following compositional operators: . $ <$ <$> $> <> <* <*> *> >> >>= =<< >=> <=< <|>.

By using them, it is possible to conveniently make an abstraction by saying f3 = f2 . f1

which is equivalent to

f3 = f2(f1()) in the point free notation.

And if this is not enough, you can always create your own operators.

What a splendid language!

Currying and Partial Application

To become a subject for the composition, functions should accept only one argument. Currying is the operation that creates a single-parameter function from a multi-parameter one. A curried function is a single-argument function that simply returns another function with the number of arguments decreased by one. On the other hand, partial application (not to be confused with partial functions) allows binding of predefined values to some function parameters, which also results in a function with a lesser number of arguments.

Lazy and Strict Evaluation

When working with recursive algorithms and data structures, it makes sense to defer the evaluation of the recursive part until it is actually needed. Such deferring based on syntactic constructs is called lazy evaluation and allows, for example, the creation of potentially infinite sequences. Such tricks are impossible in strict languages, where all expressions are evaluated completely just after they are encountered.

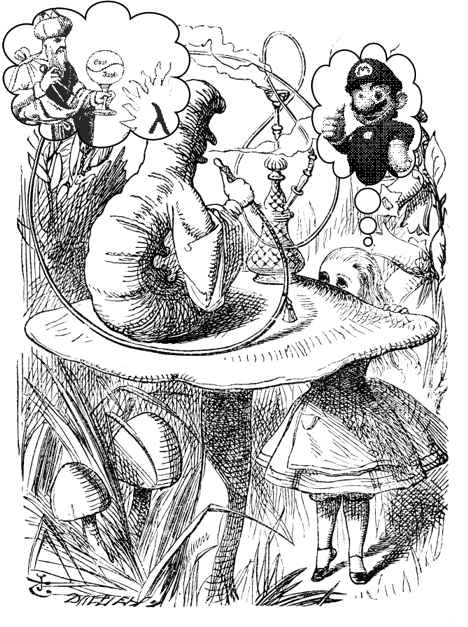

Through the Looking-Glass: Where We Meet Category Theory

Design of purely functional programs heavily relies on category theory and the underlying algebraical laws of the employed functional primitives. We will only scratch the surface here to give a glimpse of what purely functional design may look like.

Algebraic Data Types

Although functional languages may be dynamically typed, there are plenty of statically-typed ones. At first glance, functional type systems with their typeclasses (templates that define possible operations on types) may seem complex and unwieldy. It is because they may really be complex and unwieldy.

There are two kinds of algebraic data

types (ADTs): sum types and

product types. They vary in the way by which their number of inhabiting values

is calculated. For example, the number of possible inhabiting values of

2-tuple of bytes, which is a product

type, is 256x256 = 65536. It includes all possible combinations from [0, 0] to

[255, 255]. On the other hand, the number of inhabitants of the Boolean, a sum

type, is 2: true and false. Product types and sum types are collectively

called “algebraic” because they have algebraic

properties

similar to normal integers.

In practice, the sum types are often employed as containers or tags that wrap some

values which then are processed with pattern matching. Such wrappers are called “contexts”.

For example, the following listing defines the Maybe sum type with two value constructors used

as tags. Just takes a parameter and Nothing appears as is.

data Maybe a = Just a | Nothing

x = Just 10 -- wrap an Int into the Maybe container

Similar to a null-reference, the Maybe type may be used to distinguish between the

absent and fulfilled results of a computation. Because in pattern matching compiler will

enforce the implementation of the Nothing branch, it is generally more safe than the use of null,

dubbed as the billion-dollar mistake.

Pattern matching

Pattern matching offers syntactic constructs needed to destructure and recombine values stored in ADTs.

add :: Int -> Int -> Int -- Hindley-Milner signatrue declaration

add x y = x + y -- add takes two Ints and returns an Int

addmb :: Maybe Int -> Maybe Int -- addmb takes an Int packed into a Maybe

addmb x = -- and also returns an Int packed into a Maybe

case x of -- the pattern matching takes place here

Just x' -> Just (add x' 2) -- x' is the Int destructured from the Maybe wrapper

Nothing -> Nothing -- Nothing is left as it is

It is important to note, that each branch of a pattern-matching expression

spawns its own path of execution. Because exceptions disrupt the control flow

of a program, functional languages use pattern matching based on contexts to

process errors. Being returned somewhere in the middle of the chain of composed

functions that use pattern matching, Nothing will short-circuit the

computation - only the branch with Nothing will be chosen. Such change of a

computational path or of a context is called an “effect” (not to be confused

with side effects). More precisely, effect is a computation that transforms

something into something other (probably of some other type) wrapped in a context ADT.

Such ADTs are called effect types.

The two following sections contain some highly condensed abstract stuff, but it is important. Please, do not switch the channel.

Some Category Theory

A category consists of a set of objects and a set of

morphisms between the objects.

Morphism f between objects a and b is written as f: a -> b. Morphisms

compose. In the context of functional programming, objects are types and

morphisms are functions. Morphisms that map to the same type (f: a -> a) are

called endomorphisms. Morphisms may map not only between types, but also between

categories, for example:

-- a function that takes type a and returns type b is mapped to a function

-- that takes and returns these types wraped into the Maybe container

F :: (a -> b) -> (Maybe a -> Maybe b)

Such higher-order morphisms are called functors, and mapping into some other category (context) is called lifting. Morphisms that preserve the algebraic structure of the objects, as in the definition above, are called homomorphisms. There are also morphisms of functors. Nothing complex, just arrows everywhere.

Algebras

Algebras may be considered as a set of functions operating over some ADTs, along with a set of laws or constraints specifying relationships between these functions. For example, the magma is defined as a set that is closed under a binary operator. Functional programmers create algebras to formalize and verify the design of their programs.

All this “complex” algebraic stuff is actually what you learned in elementary school:

- A semigroup is a magma where the binary operator is associative.

- A monoid is a semigroup where the set has a identity element.

- A group is a monoid where every element of the set has a unique inverse element.

- An Abelian group is a group where the binary operator is also commutative.

- A semiring is an algebraic structure with set R and 2 binary operators, + and ⋅, called

addition and multiplication. It has the following laws:

- (R, +) is a commutative monoid with identity of 0.

- (R, ⋅) is a monoid with identity of 1.

- Multiplication is left- and right-distributive.

- Multiplication with 0 annihilates R.

- In a ring, the set has an additive inverse.

The successful functional design relies on the proper understanding of the algebraic properties of the corresponding constructs, such as monoid, modad or functor. For instance, a monoid has the following algebraic properties:

- Closure: <category element> + <category element> = <element in the same category>

- Associativity: (1 + 2) + 3 = 1 + (2 + 3)

- Identity: 0 + <a number> = <the number> + 0 = <the number>

Addition of integers is a monoid, so it could be used, for example, in folding without the fear of an incorrect result.

Abstractions Based on ADTs

Let’s imagine that you decided to create some abstractions by composing some functions that accept and return some ADTs. During the course of execution, they may produce some effects. Here you are entering the territory of the functional plumbing with morphisms. Unfortunately, the constraints imposed by static typying could not be satisfied automatically. Your task is to choose the right morphisms to make the chain of composed functions to work as intended. The morphisms are usually implemented as methods of the typeclass implementation for the particular context type.

Let’s assume that mayb returns an integer result of some

computation wrapped in Maybe.

mayb x = Just x -- here we just wrap x of any type into Maybe

Let’s create an abstraction addcomp, that adds an Int to the result of mayb.

addcomp :: Int -> Maybe Int

addcomp y = y + mayb 1 -- this does not work

You can not say that y + mayb 1 because there is no + operator that sums

integers and Maybe. In OOP you probably would implement such an operator or a

visitor. In FP you need to use a functor (<$>) to perform addition inside the

context of Maybe.

addcomp y = (+ y) <$> mayb 1 -- here + is partially applied

To use the functor or another morphism with your own wrapper type,

it is necessary to implement the corresponding typeclass by providing instances of

its methods such as map, fmap, mappend and others. For example, this is

how fmap of the functor typeclass instance for Maybe is implemented:

instance Functor Maybe where -- <$> seen above is the infix synonym for fmap

fmap f Nothing = Nothing -- nothing is done with Nothing

fmap f (Just x) = Just (f x) -- x is destructured from Maybe, applied to f,

-- and placed back

fmap takes a bare function, + in our case, along with a value wrapped into a

context, and applies the function inside the same context.

Sometimes computations end with functions packed inside a context. In this case,

we use applicative functor

(<*>) for plumbing. This appliance accepts the function inside a context, a

value inside a context, takes them out, applies them, and puts the result back.

For the Maybe container pure 1 returns Just 1. Watch the hands:

addcomp y = mayb (+ y) <*> pure 1 -- this implementation of addcomp produces

-- the same result as above

All compositional operators in Haskell are intended for such plumbing. To become a skilled functional plumber, it is necessary to understand the meaning of the bottomless crevasse of such magical words as functor, bifunctor, profunctor, applicative functor, invariant, contravariant, lens, Kleisli arrow, monad, and, save the Lord, comonad. In theory, all plumbing should be checked for consistency with the corresponding algebraical laws mentioned above. Do the composed functions commute? Does the identity law hold? There is even some advanced literature on this topic that promises a path to the functional nirvana.

Monads

No text on functional programming could avoid the topic of monads . Monads are truly magical. They allow chaining sequential computations that produce effects. They even allow performing side effects or input/output, which are considered impure operations.

What are monads?

Monads are monoids in the category of endofunctors, which, as you remember, are

semigroups with identity. This means that they are also functors. Particularly,

applicative ones. If this does not make things clear, monads just allow to

compose functions of the form f: a -> m b, which are called monadic or

effectful functions. Here m is a context for which you need to implement a

monad typeclass instance, and, as the signature suggests, the type b may be

completely different from the type a. For an example, let’s create a monadic

function that returns the reciprocal of the given number:

reciprocal :: Int -> Maybe Double

reciprocal 0 = Nothing

reciprocal x = Just $ 1 / (fromIntegral x)

Because the addcomp function from the example above is also monadic, we

can compose them using the monadic bind (»=):

moncomp = addcomp 1 >>= reciprocal -- in the point-free notation

-- the argument is assumed

The call moncomp 1 will result in Just 0.5.

All the magic happens in the context’s implementation of bind.

This is how bind for Maybe is implemented:

instance Monad Maybe where

...

(>>=) :: m a -> (a -> m b) -> m b

Just x >>= f = f x

It takes a value in a context and a monadic function, so the result remains in the context. Monads may bring their own problems: the contexts may stack like onion petals, and additional plumbing may be required to peel them off.

What is so fancy about all this?

When looking at combinators modelled as a workflow which represents some business rules, some people compare them whit prose, poetry, or haiku:

prepareForm templateURL = do

reportErrors

downloadTemplate

insertCurrentDate

trimFields

When the composition is used along with pattern matching, we also get error processing almost for free, and there are no ugly try/catch blocks around every function call. An error simply short-circuits the happy execution path. Tiny functions with focused responsibilities facilitate code malleability. Although, since functions need to be curried, and the plumbing logic may be scattered across typeclasses, there are some limits.

Afterword

OOP programmers just declare properties in their classes to maintain state.

In functional programming, state is avoided whenever possible. But when it is impossible,

functional programmers are bound to pass monads

in and out. They usually stash state somewhere

in tuples along with the results of their computations. Does this help to create

clear, comprehensible, and maintainable designs? It is for you to decide. And

users of the dynamically-typed functional languages do not learn category

theory. They just use the comp function to compose. It is barely imaginable,

how they are able to write working programs with this.